The Mississippi River Basin Model, located in the Buddy Butts Park near Clinton, Mississippi, was built as a large-scale hydraulic model of the entire Mississippi River basin and it covers an area of 200 acres. It took from 1943 to 1966 to build it and the experiment station was in operation from 1949 until 1973. The model is now overgrown, but it you can still visit the station from within the Buddy Butts Park.

In the early 1970’s when I was a child, I remember being taken on a school field trip to see the model, but it is a very vague memory and I’m not really sure I understood the full gravity and impact of the model. I remember concrete valleys with small boxes and bumps that I think were indications of obstructions and sand bars located in the real river. They let some water flow through the model in one area, but they didn’t fully load the model because the cost was too high.

Large scale, localised flood control measures such as levees had been constructed since the early 1900s, especially in the decade after the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 and following the Flood Control Act 1936. From 1928 onwards, the Army Corps of Engineers built a huge number of locks, run-off channels and extended and raised existing levees, but these control measures only targeted single sites, and did not look at the entire river system.

There had already been extensive modelling of individual sections of the river at the Waterways Experiment Station in Vicksburg, including a 1060 ft long model of the 600 river miles from Helena, Arkansas to Donaldsonville, Louisiana, but in early 1937 it was clear that impact of control measures were not completely successful.

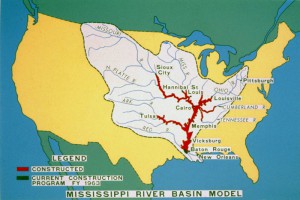

In 1941 Eugene Reybold proposed a large-scale hydraulic model which would allow the engineers to simulate weather, floods and evaluate the effect of flood control measures on the entire system. This would cover approximately 200 acres, include all existing and proposed control measures, and a network of streams nearly 8 miles in total length.

In her March, 2011 article “The Scale of Nature: Modeling the Mississippi River“, Kristi Dykema Cheramie points out that in 1928 Congress passed the Flood Control Act of 1928 in response to the Mississippi River flood of 1927 which then Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover called “the greatest peace-time calamity in the history of the country.” In the next decade, the Army Corps of Engineers built 29 dams and locks, hundreds of runoff channels, and over a thousand miles of new, higher levees. But the River was not an easy enemy to beat and in 1936 floods in the Northeast displaced hundreds of thousands of people, so in response public outcry, Congress passed the Flood Control Act of 1936 which treated flood control as a “national defense” and provided federal funding for levees, dams, reservoirs and dikes. Implementation of flood control was turned over to the Army Corp of Engineers.

As work began along the Mississippi River basin, it became clear to Major Eugene Reybold, a district engineer in Memphis, Tennessee, that there was really no way to keep up with the effects of all the changes being made or to test proposals so he came up with the idea of a large-scale hydraulic model that would enable engineers to observe the interactive effects of weather and proposed control measures over time and “develop plans for the coordination of flood-control problems throughout the Mississippi River Basin.” In 1943, the Army Corp of Engineers approved Reybold’s plan and the construction could begin.

As work began along the Mississippi River basin, it became clear to Major Eugene Reybold, a district engineer in Memphis, Tennessee, that there was really no way to keep up with the effects of all the changes being made or to test proposals so he came up with the idea of a large-scale hydraulic model that would enable engineers to observe the interactive effects of weather and proposed control measures over time and “develop plans for the coordination of flood-control problems throughout the Mississippi River Basin.” In 1943, the Army Corp of Engineers approved Reybold’s plan and the construction could begin.

The site selected was near Clinton, MS most likely because there was already a Waterways Experiment Station located in Vicksburg (sorely underfunded), but the amount of flat land needed was not available in the Vicksburg area. Heading due East from Vickburg, Clinton, MS had a large area of land available and it was ideally situated between Vicksburg and Jackson.

Once the land was selected, the next question was how would Reybold come up with enough manpower to build the massive model in the middle of World War II with most able bodied men off fighting the war and the rest of the work force in manufacturing plants producing ammo and weapons. Reybold negotiated for the transfer of German & Italian Prisoners of War that had been housed stateside to a new internment camp he would build and then he would use their labor to build the giant model.

According to Cheramie’s article:

The prisoners cleared the site of a million cubic yards of dirt and rough-graded the land to match the contours of the Mississippi River Basin. To ensure that topographic shifts would be apparent, the model was built using an exaggerated vertical scale of 1:100 and a much larger horizontal scale of 1:2000. While the existing topography offered a close approximation of the actual Mississippi Basin, some areas required significant earthmoving; the Appalachian Mountains were raised 20 feet above the Gulf of Mexico, the Rockies 50 feet. An existing stream running east-to-west provided the model’s water supply. The streambed was molded to take on the shape and form of the upper reaches of the Mississippi, and a complex system of pipes and pumps distributed water throughout the model; it was regulated by a large sump and control house sited near what would become Chicago, Illinois. To simulate flood events, Reybold needed to introduce large volumes of water over short periods of time, so he designed a collection basin and 500,000-gallon storage tower system at the model’s edge. Small outflow pipes at anticipated data collection points channeled excess water to 16 miles of storm drains.

[..]On April 1, 1952, George Stutts, a Missouri River engineer, conducted his regular field surveys of the levees in Nebraska and reported that northwest Missouri was in “no immediate danger of flooding.” Only seven days later, a new survey indicated signs of imminent and severe floods. The mayors of Omaha and Council Bluffs contacted the Army Corps District Office to propose using the basin model to predict flood stages, and the model was called into active duty for the first time.

On April 18, as the Omaha World Herald rolled out the headline “Missouri River Near Crest Here; Anxious Eyes On Soggy Levees,” the basin model was halfway through 16 days of continuous 24-hour tests. Engineers issued prototype conditions to the newly installed instruments, generating simulations that forecasted likely events over the next month — crest stages, discharges, levee failure and more. As water poured through the Missouri River section of the model, the resulting data were relayed directly to aid workers in Omaha and Council Bluffs, who were able to respond with brigades of civilians and sandbags to points where levees needed to be raised only slightly; areas predicted to flood dramatically were evacuated. In total the Mississippi River Basin Model prevented an estimated $65 million in damages.

With this impressive victory against the river, Reybold’s project was vindicated. The model had allowed the Mississippi River Basin to become, for the purposes of study, an object, a manageable site. Here engineers, community leaders and civilians could gather to discuss the potential ramifications of particular flood control measures and forecast likely scenarios. Each gallon of water passing through the model was the equivalent of 1.5 million gallons per minute in the real river, meaning one day could be simulated in about five minutes. This allowed for a tremendous capacity to collect data, to use the model as an active tool for communication, and to distribute information about the river as a system. With mayors from cities up and down the river gathering in the observation tower to watch the Mississippi cycle through an entire flood season, it became possible to find edges, limits and centers, to see how and where the river might strike next. The model imbued the river with a reassuring degree of certainty. Policymakers began to adjust to a new scale of thinking.

Although it has fallen into disrepair and is very much overgrown with weeds and brush, the site can still be toured and you can see reminders of the care, work and effort that the Army Corp of Engineers put into the The Mississippi Basin Model in order to protect property and lives. Before the days of computer modeling, it was the only and best way to predict flood events along the Mississippi River Basin. It is a marvel of engineering and a life saver. It helped the Corps learn more and help more people than it had ever been able to do before.